Nikola Tesla's Investigation of High Frequency Phenomena and Radio Communication (Part II)Donald Mitchell Pelican Rapids, Minnesota, 1972

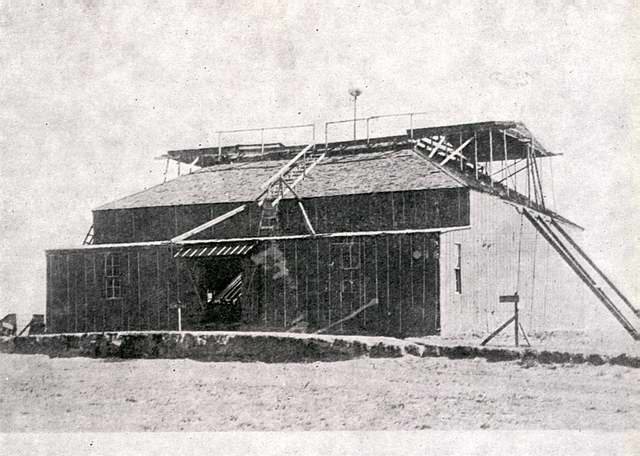

The Colorado Springs LaboratoryBy 1899, the laboratory in New York was too small to carry out the further experiments needed to answer the questions about the earth's electrical properties and resonant frequency [40]. Tesla wanted to work with much more powerful oscillators, and his lab was already too small for the big spiral coil. When operated at 3 million volts, it sent arcs out striking the ceiling and walls.The solution to Tesla's problem came when Leonard E. Curtis, of the Colorado Springs Electric Company, offered him the use of some land on Knob Hill near Colorado Springs [41]. He also gave Tesla free electricity for his experiments. After receiving large donations from several wealthy friends, Tesla arrived in Colorado Springs on May 18, 1899 along with a number of trusted assistants and his chief engineer, Fritz Lowenstein [42]. In New York, Tesla left George Sheriff in charge of the lab and the construction of some equipment that was later shipped to Colorado. Tesla hoped to build an oscillator many times more powerful than anything he had worked with before. He was certain that it would be adequate to determine if resonance effects could be produced in the earth, and even more important, to make high powered tests of wireless communications systems. Upon reaching Colorado Springs, Tesla began the construction of his laboratory. The building itself was a square, barn-like structure about 80 feet square [43]. The walls were about 20 feet high, sloping up to 35 feet at the top. On top, sliding panels rolled back to make an opening in the roof (below).

Before the oscillator was completed, Tesla was performing experiments with a sensitive receiving device with which he was investigating the electrical activity of the earth. The device consisted of a primary coil with a large number of turns, the bottom of which was grounded and the top connected to an elevated terminal of adjustable capacity [44]. In a secondary circuit, made up of several turns of wire near the base of the primary, a sensitive detector was located (the detector was a coherer). [DPM - Coherers were a vacuum tube filled with powdered metal which conducted electricty when exposed to radio frequency energy] With this apparatus, Tesla claimed to have discovered an important clue to his mystery. Tesla described the incident as follows: "It was on the third of July--the date I shall never forget--when I obtained the first decisive experimental evidence of a truth of overwhelming importance for the advancement of humanity. A dense mass of strongly charged clouds gathered in the west and towards the evening a violent storm broke loose which, after spending its fury in the mountains, was driven away with great velocity over the plains. Heavy and long persisting arcs formed almost in regular time intervals. My observations were now greatly facilitated and rendered more accurate by the experiences already gained. I was able to handle my instruments quickly and I was prepared. The recording apparatus being properly adjusted, its indications became fainter and fainter with the increasing distance of the storm until they ceased altogether. I was watching in eager expectation. Surely enough, in a little while the indications again began, grew stronger and stronger and, after passing thru a maximum, gradually decreased and ceased once more. Many times, in regularly recurring intervals, the same actions were repeated until the storm, which, as evident from simple computations, was moving with nearly constant speed, had retreated to a distance of about three hundred kilometers. Nor did these strange actions stop then, but continued to manifest themselves with undiminished force. Subsequently, similar observations were also made by my assistant, Mr. Fritz Lowenstein, and shortly afterwards several admirable opportunities presented themselves which brought out still more forcibly and unmistakably, the true nature of the wonderful phenomenon. No doubt whatever remained: I was observing stationary waves [45]."Tesla believed that this proved the earth acts as a body of finite dimensions and could be made to resonate. The disturbance of the lightning created ripples or waves that would spread out and affect any receiver with equal strength as they passed by if the earth acted as an infinite conductor. However, when the waves that Tesla measured spread out and then were reflected and superimposed, they formed nodes where they were much stronger than elsewhere. The simple fact that the waves could be reflected proved that a resonant condition could be produced if a powerful signal was in tune with the planet. The waves detected by Tesla in the lighting storm experiment were 25 to 75 kilometers long [46]. The success of Tesla's idea for transmitting current through the earth depended entirely on whether or not stationary waves had really been observed. The effects, which will shortly be described, did not necessarily require stationary waves and, in fact, can be explained in other ways. Tesla's theories of ground transmission of electric waves are not generally accepted today, but this should not be allowed to belittle his accomplishments.

The Magnifying TransmitterNot a great deal is known about the apparatus that Tesla used in his Colorado laboratory, but pictures and articles written by Tesla have supplied some information. During the construction, Tesla kept in touch with the lab in New York, where much of the equipment was being made. In letters to and from George Sheriff, some of the equipment is discussed. New York was shipping balloons eight and ten feet in diameter and covered with varnish. 300 bottles with the necks ground off (probably for leyden jars), drums, oscillators and spools, 1100 feet of solid wire, and later 40,000 feet of cable. A number of storage batteries were also sent, along with nickel and aluminum chips and five grades of silver and gold filings for coherers. Inside the lab there was a small machine shop and an office. Tall coils and strange electrical devices crowded the building, but the giant oscillator in the middle of the main room dominated the scene. Tesla called this new type of coil a Magnifying Transmitter. He believed that it would create stationary waves of electricity that would encircle the globe and allow the transmission of intelligence and possibly even power through the ground without wires. Basically it was a giant Tesla coil, but with modifications in design to allow it to deliver incredibly high voltage.

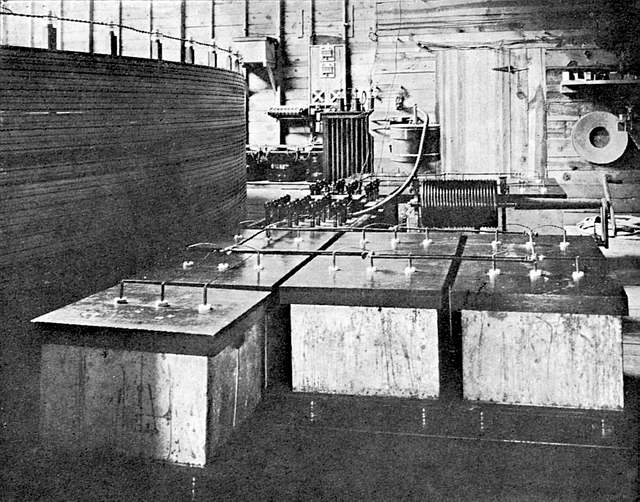

Along one wall of the lab, power cables, meters, switches, and the twelve storage batteries were located. Besides the secondary coil of the Magnifying Transmitter was the primary oscillator that energized it (above). This oscillator was far more powerful than the ones used today for most AM radio stations. At full capacity, it drew over 800 amperes from the power lines and delivered up to 200,000 watts to the transmitter. The low voltage line current was stepped up by 50,000-watt transformers (there may have been only one since Tesla rarely approached the 200 KW level), which were designed to give 60,000 volts. Tesla retapped them, however, to give 20 or 40 KV. The transformers charged a bank of high-tension condensers made up of 13 tanks of oil with copper plates immersed in them and two more tanks with 16 leyden jars each (also immersed in oil for insulation and cooling). The condensers were discharged through the primary coil by means of a very heavy-duty 25-tooth rotary circuit breaker. The primary circuit also contained a variable induction coil (seen above the condensers above) which consisted of 24 turns of heavy cable wound on a drum and could be adjusted by a crank from zero to 100 micro henries. The primary coil itself was a single turn of stout cable 17 meters (51 feet) in diameter embedded in the floor. Directly above the primary coil was a 51-foot circular wooden wall about seven or eight feet high upon which the secondary coil was wound. This had 25 or 30 turns of thick wire spaced with several inches between each turn. The top turn was suspended six or eight inches above the wall on glass telephone insulators. A second smaller coil was located in the center of the space enclosed by the wall. This coil was ten feet in diameter, ten feet high and stood three feet off the floor. 100 turns of wire were wound on this coil. A heavy wooden post was driven into the ground and extended up through the center of the coil to a height of about 20 feet. From there a metal pipe with a copper hood at the base to prevent corona loss rose up through the opening in the roof making a total height of nearly fifty feet. Nothing is known about the regulatory systems on this giant coil, but if it is anything like earlier models, then it was probably very highly controllable. The variable induction coil and changes in the number of condenser tanks and leyden jars used would have allowed a wide range of operating frequencies. Varying the speed of the rotary break and the voltage used in charging the condensers could have controlled power. There was almost certainly a variable choke coil between the condensers and the transformer to control power, prevent short-circuiting and high frequency feedback into the power lines.

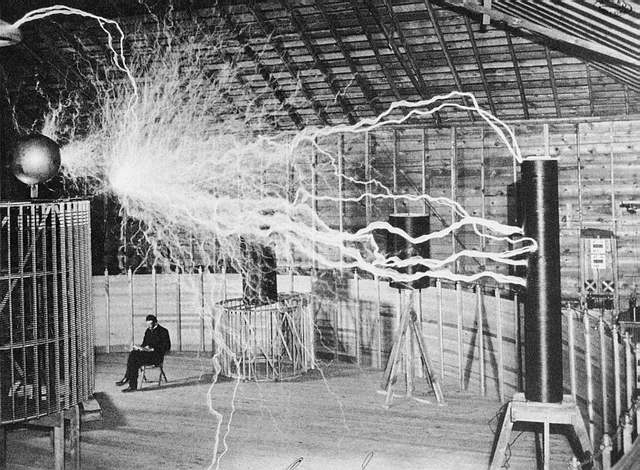

The most important experiments were carried on with the Magnifying Transmitter by itself without the ten-foot coil. In experiments carried on inside the lab, an 80 centimeter copper sphere mounted on a stand was used as the terminal. In the photo above [DPM - a double exposure], this set-up can be seen operating. Discharges of 20 or 30 feet could be produced easily by this coil, indicating 4 or 5 million volts. The most amazing thing about this coil was that, even though it was only eight feet from bottom to top, it could produce 30-foot arcs without shorting out. Tesla's technique for accomplishing this is beautifully ingenious. The coil's ability to produce 5 million volts is not unusual since the voltage is proportional to the inductance and inversely proportional to the capacitance, and this coil with its large diameter and widely spaced turns has much of the former and very little of the latter. Naturally the voltage is dependent on scores of other factors as well. To prevent the coil from discharging from top to bottom, Tesla used two techniques. The first was to eliminate any sharp corners, which would cause corona loss and, when very high voltage is used, cause an arc to burst out into space. Round hoods were placed over any relatively sharp edges (such as the base of the pipe that extended through the roof). The coil itself had little corona loss because of its extremely large diameter. [DPM - a quarter wave coil develops high voltage at the capaciter at one end, while energy takes the form of current within the coil.] The other trick that Tesla used was to create a path of very little resistance for the current, so that it would follow the wire to the 80 centimeter ball instead of jumping out at some other point in the circuit. In very high voltage experiments, an inverted metal pan was attached to the base of the ball and its dimensions were such that it would cause the arc to break out from it when the voltage was a maximum. The cable used in winding the coil was very thick copper and probably had a resistance of only a few ohms. This situation was highly unstable. Tesla was literally steering a lightning bolt, so great care had to be exercised. One of the most delicate problems was to keep the coil tuned properly. If the frequency impressed by the primary coil strayed too high, impedance would result in the secondary. This added resistance could cause the current to take a shorter path through the air. Tesla had a number of narrow misses with flaming discharges of inconceivable violence. Although high frequency current cannot electrocute a person in the normal sense of the word, the high currents would burn him to a crisp. The laboratory building was also set on fire several times in this way, but fortunately, Tesla had equipment to combat it. To prevent these accidents, the Magnifying Transmitter had to be started with care. The power was increased gradually and the frequency was carefully monitored. These effects demonstrated a new degree of resonance. Here was resonance so efficient and on such a large scale that it could reach dangerously high levels. Tesla once described the Magnifying Transmitter in these words: "This is, essentially, a circuit of very high self-inductance and small resistance. The electromagnetic radiations being reduced to an insignificant quantity, and proper conditions of resonance maintained, the circuit acts like an immense pendulum, storing indefinitely the energy of the primary exciting impulses and impressing upon the earth uniform harmonic oscillations of great intensity." [47]According to Tesla, the Magnifying Transmitter could operate in two modes. These were with damped or undamped oscillation. In the undamped mode, a continuous wave would be produced. To do this, Tesla probably used the same methods that he applied to his smaller oscillators before. Basically, this would involve increasing the rate of the rotary break so that the condenser discharges with great rapidity. The frequency at which the Magnifying Transmitter was usually operating was at 150 KHz for maximum voltage. Since most of the earlier rotary breaks operated at only a few thousand times per second, the wave train at this frequency would fade out between impulses. However, by this time Tesla had perfected his mercury interrupters (the type he generally used) to a much higher level. Some of them were able to handle up to 50 horsepower at a rate of 100,000 impulses per second [48]. This would allow the primary circuit to feed impulses to the secondary so fast that each impulse would arrive before the preceding one had faded out. The system may have been identical to the timed spark system patented by Marconi in 1912 [49]. Other modifications were undoubtedly made to allow for such a rapid charging of the condensers. The transformer may have been set at 20 KV and the ratio of capacitance to inductance would be made as low as possible, but still maintaining the 150 KHz frequency. These things would create a situation in which a small amount of capacitance would be charged with a relatively lower voltage but at a very high rate. This produced very constant oscillation but at a fairly low voltage. In fact, there was almost no noise or discharge produced. Although very low voltage (still many hundreds of thousands of volts) was created, the amperage was extremely high. At one time, Tesla measured 1,100 amperes, which would have meant 110,000 horsepower has been reached in the violently resonating circuit. Damped oscillation produces a wave train made up of very intense impulses, which fade out rapidly before the next impulse begins. It is logical to assume that Tesla adjusted the primary circuit to have a greater capacitance and less inductance (still tuned to 150 KHz). The voltage of the transformer would be stepped up to 40 KV (a condenser charged to twice a given voltage will hold four times the energy), and the circuit breaker would have to be slowed down. In this instance, the incoming energy would be used to charge a very large capacity less often than for the undamped oscillations, and thus produce extremely intense impulses. The usual precautions would be taken to handle very high voltage. Tesla was certain that the Magnifying Transmitter could produce voltages far above the 5 million volt level if enough power was used. To see how high the voltage would go, he connected the secondary coil to a copper sphere one meter in diameter that was located on the pole that extended up through the roof. As in most of his experiments, Tesla was forced to wait until after midnight before he could draw the heavy loads that he needed from the powerhouse. In earlier experiments in New York, Tesla had noticed that the high-frequency discharges made by his oscillators showed a marked tendency to shoot upwards into the air. This could have been caused by electrostatic effects or simply by rising of the ionized air that had been violently heated by the discharges. When the Magnifying Transmitter was running, it caused a very strong updraft through the opening in the roof. Tesla hoped that this effect would allow him to generate extremely high voltages without any danger of arcs striking the lab. When the power was increased to maximum, arcs of 50 to 70 feet were produced, which leaped off the ball and up into the air. Some of the impulses were even more powerful and discharges of over 100 feet were recorded! (The arc lengths were determined by comparisons to the height of the lab in photos take of the arcs) [50]. These discharges were so loud that they were heard ten miles away. The record-breaking arc lengths were created by potentials as high as 18 million volts. This may be the highest voltage ever produced by a generator of electric current. The power consumption of the oscillator in producing 18,000,000 volts was highly prohibitive. In the first full power trial, the dynamo in the powerhouse started on fire. Tesla and his assistants graciously repaired the generator, but that was the end of free electricity for Tesla.

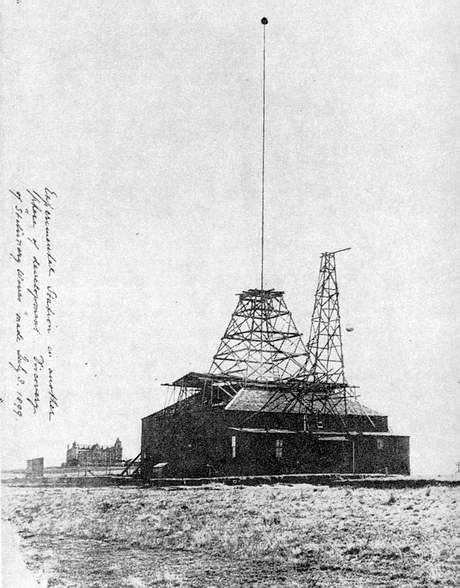

After the first experiments, Tesla added on to the laboratory building. Two derrick shaped towers rising up to 80 feet above the ground were built onto the roof of the building (above). A narrow tower was built up from the side of the lab just over the area where the primary oscillator was located. At the top was a beam with a ball hanging from it. The purpose of this is unknown. The other structure, which was much wider, was built over the opening in the roof and was used primarily to support a 200-foot mast with a one meter copper ball at the top. This mast was an extension of the 50-foot pole used in earlier experiments described. It was made up of sections of metal pipe that could be quickly dismantled in case of a sudden electrical storm.

Experiments And ResultsThe most important part of Tesla's stay in Colorado was, of course, his experiments and the discoveries he made. Unfortunately very little is known about these except from articles written by local newspapers and, later, in articles written by Tesla. The notes that do exist were never published and are now stored in the Nikola Tesla Museum in Beograd, Yugoslavia [51]. [DPM - some notes published in 1978] In one experiment described by Tesla, a square wire loop 50 feet on a side was laid out on the ground 100 feet from the oscillator. In the loop were three large incandescent bulbs in series and a tuning capacitor shunted across the bulbs. When the oscillator was operated at 5 percent power, the bulbs were lit to full brightness. In addition to this experiment, Tesla described a number of very unusual phenomena caused by the Magnifying Transmitter. When the secondary coil was fully energized, the ground around the laboratory was highly charged. At night, the ground shimmered with an eerie blue glow from sparks between the grains of sand. A person walking near the building would notice sparks forming between his feet and the ground. When the coil was operating at 4 million volts, Tesla could stand 60 feet from the lab and hold a light bulb. The filament would vibrate with such violence that it would quickly shatter. One amusing effect was that butterflies would sometimes be caught up and whirled around the building as if in a hurricane. Strange as it may seem, small Tesla Coils and Van DeGraff machines cause a similar display with small bits of foil. Tesla realized from experiments in Colorado that power transmission would probably not be practical through the earth alone, but he was still able to produce some startling demonstrations of this within a radius of 25 mils or so [52]. When the secondary coil was producing 20 to 30 foot discharges as described earlier, the ground near the lab would be disturbed so strongly that arcs of an inch in length could be drawn from a water main 100 feet away. When operated in the undamped mode, horses a half a mile away would be spooked by minute shocks received thought their hooves. At full power, lightning rods 12 miles away would be bridged by small but continuous arcs. The most dramatic experiment with broadcast power was the lighting of 200 light bulbs at a distance of 26 miles [53]. This involved the transmission of about 10,000 watts without wires. As impressive as all this sounds, the range of the transmission was not great enough for worthwhile power distribution. Tesla never completely abandoned the idea and, in some later articles, he said that it might be practical with bigger transmitters. Without know the details of Tesla's discoveries in Colorado, it would really be impossible to say that he was wrong. The real reason that Tesla went to Colorado was to test his wireless signal transmitter. He said before he even left for Colorado that when he returned he would build a transmitter in New York that could reach Paris [54]. Using special detectors, Tesla was able to receive impulses from the Magnifying Transmitter at a distance of 600 miles [55]. This is far in advance of anything done by other experimenters working at that time. It may seem impossible that so much power could be radiated from the oscillator used by Tesla with its 200-foot mast to act as an antenna (Assuming that Tesla's theory of earth conduction was wrong). In fact though, it is not unusual. The amount of power radiated by an aerial is equal to the square of the antenna current times the radiation resistance of the antenna [56]. At 150 KHz, a 200-foot antenna would have a radiation resistance of only about two ohms. This is not very good for an antenna, but with the extremely high current developed by the Magnifying Transmitter, it would not be hard to believe that great quantities of power were transmitted. Besides these factors, there was also an advantage in using low frequencies and short antennas since these things encourage strong ground wave radiation [57]. Tesla stated that he was also studying the electrical properties of the rarefied mountain air to see if his system of transmitting power though the atmosphere would be practicable. Nothing is known about these experiments, but they may have involved highflying balloons, which Tesla said he used for some kind of experiment. When Tesla returned from Colorado, he said that aerial power transmission would definitely work on an industrial scale.

Notes For Part II40. John J. O'Neill, Prodigal Genius: The Life of Nikola Tesla New York, Ives Washburn Inc., 1944, p 165. 41. Ibid., pp 175, 176. 42. New York Tribune, May 19, 1899, III, p5:1, and O'Neill, Op. Cit., p 176. 43. Note: The exact dimensions of the lab are not known. A number of approximations have been made, however, from photographs. 44. Nikola Tesla, "Transmitting Electrical Energy Without Wires, Scientific American, June 4, 1904, supplement. 45. Ibid., supplement. 46. Patent No. 787,412, "Transmitting Electrical Energy Through the Natural Mediums", April 19, 1905. 47. 44. Nikola Tesla, "Transmitting Electrical Energy Without Wires, Scientific American, June 4, 1904, supplement. 48. Samuel Cohen, "Dr. Nikola Tesla and his Achievements", Electrical Experimenter, February 1917, p 713. 49. "Guglielmo Marconi", Encyclopedia Britannica, 19780, XIV, p 856. 50. "New Inventions By Tesla -- Address at meeting of New York Section of National Electric Light Association, May 15, 1911, Electrical Review (New York), May 20, 1911, p 987. 51. Nikola Tesla: Lectures, Patents, Articles, Beograd, Yugoslavia, Nikola Tesla Museum, 1956. 52. "Can Radio Ignite Balloons?", Electrical Experimenter, October 1919, pp 591, 592. [The context is observation balloons used in WWI] 53. O'Neill, Op. Cit., pp 193, 194. 54. Colorado Springs Gazette, May 19, 1899, p 3. 55. Nikola Tesla, "The Problem of Increasing Human Energy", Century, June 1900, p 209. 56. R. S. Glasgow, Principles of Radio Engineering, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1936, p 434. 57. Ibid., p 499. |