|

The world's first artificial Earth satellite was a major technical and political achievement by the Soviet Union. It was built in a hurry to beat the Americans,

but space science had been underway for a decade in the Soviet Union, and a series of more sophisticated spacecrafts were nearing completion.

Soviet science in the 1950s and 1960s was dominated by three powerful personalities: Sergei Korolev headed the space program, Igor Kurchatov headed the atomic weapons laboratory, and Mstislav Keldysh was the president of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Their agendas were closely linked. Both Keldysh and Kurchatov needed Korolev's long-range rockets, and Keldysh focused the Soviet academic community on strategic tasks like space flight and atomic energy.

Scientific applications of space flight began in the Soviet Union in 1948, using R-1, R-2 and R-5 missiles as vertical sounding rockets. Experiments carried to an altitude of 100-500 km included Earth photography, solar ultraviolet and X-ray measurements, cosmic-ray detectors, animal experiments, chemical and mass-spectrometric analysis of the ionosphere, micrometeorite sensors and reentry-vehicle studies. At best, these experiments had about 10 minutes of time in outer space to carry out their tasks. In March of 1954, Keldysh, Korolev and Tikhonravov discussed the idea of orbiting an artificial Earth satellite. Two months later, they proposed to the Soviet government that a satellite be lunched before the start of the International Geophysical year (1957-1958) and specifically before the Americans did it. Keldysh became chairman of the commission to plan an orbiting "automatic laboratory", and Tikhonravov lead a team in OKB-1 to design a large and complex satellite weighing over a ton, code named Object D. As development of the scientific satellite Object D dragged on, Korolev became concerned that they might not beat America into space. In November 1956, he directed his bureau to consider two simple satellites named Object PS-1 and PS-2 (prosteishii sputnik, very simple satellite), and on February 1957 development was given an official go-ahead. Mikhail Khomyakov was the chief designer of Object PS-1.

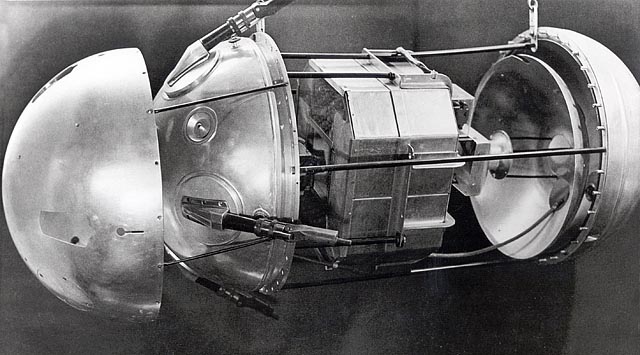

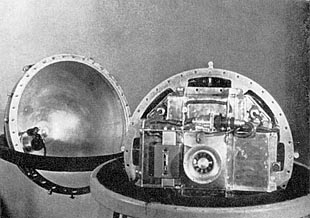

Object PS-1, Disassembled

Object PS-1, Disassembled

PS-1 was a spherical satellite 58 cm in diameter and weighing 83.6 kg. It contained two 1-watt radio transmitters and three silver-zinc batteries, two powering the radio and one for a ventilator fan. Two aluminum hemispheres 2mm thick were joined with 36 bolts and a rubber seal. A highly polished 1mm thick thermal shield covered one hemisphere (seen on the left above), providing a strongly insulating double layer. The other hemisphere was anodized to adjust its reflectivity to remain cool while in space. The sphere was filled with dry nitrogen gas at a pressure of 1.3 atmospheres. If the internal temperature rose above 30° C, the fan would start circulating the air around the cooler outer shell, turning off when the temperature dropped below 23°.

Four whip antennas formed an angle of 70°. Two were 2.4 meters long and two were 2.9 meters. The radios transmitted a signal that alternated between 20.005 MHz and 40.002 MHz, spending 0.3 seconds at each frequency. Konstantin Gringauz had done research on radio propagation and the ionosphere, and he proposed the two-frequency scheme. In particular, it was not known what the critical frequency of the ionosphere was in the upper F layer, or if this would interfere with radio transmissions between outer space and the ground. Scientists were also interested in the problem of overheating or damage from micrometeorites in space, so if the internal pressure dropped below 0.35 atm, or if the temperature went outside the range of 0° to 50° C, the radio transmitter would change to a pattern of 0.2 sec at one frequency and 0.4 seconds at the other.

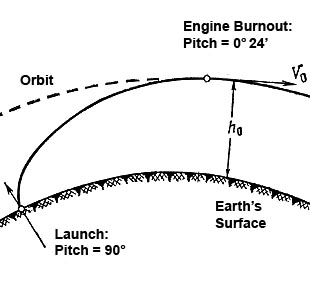

Injecting a satellite into orbit required an entirely new pitch-angle cyclogram for the R-7, a precisely shaped cog that controlled pitch as a function of time. At take-off the rocket travels on a nearly vertical trajectory, getting away from the friction of the lower atmosphere as quickly as possible. However, to achieve orbit, a high velocity (about 8 km/sec) must be imparted perpendicular to the vertical, and at engine shut down ("burnout"), the optimal pitch angle would be as close to zero as possible. An optimized program of pitch angle was calculated at the Steklov Institute of Applied Math. The R-7 contained a uniaxial stabilized platform, the V-142 gyrohorizon, to measure pitch angle and keep it in line with the programmed course. This contained an accelerometer, which was kept oriented along one axis of rotation during flight. A similar gyroverticant maintained zero yaw and roll. This was considerably more precise than the free gyroscopes used by Goddard and later on the German V-2. Speed was measured by the V-139 accelerometer, which worked by measuring the force of precession of an unbalanced gyro. This regulated engine thrust and integrated to calculate a current velocity. Engine burnout was programmed to occur at a specific final speed, which was fine tuned by the vernier engines after main-engine shutdown. Even more accurate guidance was obtained by measuring and controlling the rockets acceleration with ground-based radar and computers.

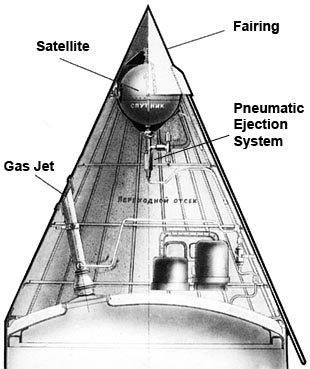

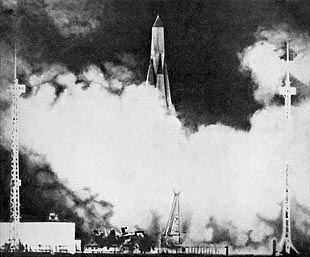

The satellite was mounted in a special nose cone, replacing the warhead of the R-7. About 20 seconds after engine burnout, a spring would eject an 80 cm conical fairing, then gas pressure from the liquid-oxygen tank would push the satellite out on a piston. A pyrotechnic ejection system was also installed as a back-up, in case the pneumatic system failed. A strong gas jet of oxygen was then fired, pushing the sustainer stage farther away from the satellite to avoid interference as the two bodies orbited. PS-1 was launched at night, on October 4, 1957 at 19:28:34 GMT. On schedule, booster separation occurred 116.38 seconds into the flight, and sustainer stage burnout occurred at 314.5 seconds. The R-7's booster-tank balancing system failed, which caused increased fuel consumption and a slightly early engine burnout. The apogee was thus 80 to 90 km lower than planned. The elliptical orbit of the satellite had an perigee of 228 km, an apogee of 947 km, and an orbital inclination of 65.1 degrees from the equator. It completed a revolution in 96.17 minutes. The larger sustainer stage tumbling through space remained in orbit for 882 revolutions, and fell on December 2. Corner reflectors installed on the rocket had permitted its accurate tracking with radar. The sustainer stage was a bright object, observed by many people and generally mistaken for the satellite itself, which was only barely visible. The satellite was tracked, and the decay of its orbit provided new knowledge about the density effects of the extreme outer atmosphere. It's spherical shape had been chosen specifically to permit an easy theoretical analysis of drag. By December 25, its perigee and apogee can declined to 190 km and 458 km respectively. It fell to Earth on January 4, 1958, after completing 1400 orbits. Its radio signal lasted for three weeks and never changed pulse frequency to indicate a drop in pressure. This was an important demonstration that micrometeorite damage might not be a major problem for future spacecrafts.

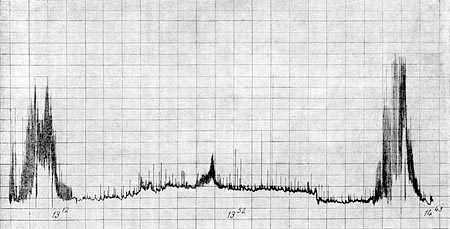

Sputnik Signal Measured from Soviet Antarctic Base The 20 MHz signals from sputnik did not fall below the critical frequency of reflection by the ionospheric plasma, and it was sometimes picked up at distances as great as 10,000 to 15,000 km. Seen above, the satellite's signal was received from the Soviet base in Antarctica. The two strong peaks show its closest approaches, while a small peak in between them demonstrates the antipodal effect known to shortwave broadcasters, a rise in signal strength when the satellite is refracted and reflected from the opposite side of the Earth. Scientists had studied the ionosphere by measuring the reflection of radio waves sent from the ground, but little was known about the electron density above the highly ionized F layer. From hundreds of radio occultation measurements (radio rise and radio set of Sputnik), the F layer of the ionosphere was estimated to extend from 200 km to 320 km. Electron density was measured from 200 km to 3100 km. The artificial Earth satellite, called iskusstvennyi sputnik zemli in Russian, was quickly dubbed "Sputnik" in the West. The political consequences of Sputnik were profound. To military experts, it was a public demonstration that Russia possessed a rocket considerably more powerful than anything yet built in America, easily capable of delivering a nuclear weapon. The general public reacted with excitement, which even Soviet leaders underestimated. Premier Khrushchev was delighted by the news of the satellite's launch and surprised by the intensity of the world's reaction. Both the USSR and the USA gave space exploration a new priority after this event. The radio signal from Sputnik-1 was specifically meant to be heard by ham radio enthusiasts throughout the world. Soviet popular science publications described how to listen to satellites, well before the launch. The satellite signals were unmodulated, but frequencies were chosen to be heterodyned in the receiver, with exactly 20 or 40 MHz, yielding an audible tone. Variations in pitch were due to the Doppler effect. |

Sounding-Rocket Capsule

Sounding-Rocket Capsule

Korolev, Kurchatov and Keldysh

Korolev, Kurchatov and Keldysh

Satellite Internals and Fan

Satellite Internals and Fan

The Finished Satellite

The Finished Satellite

Launch Trajectory to Orbit

Launch Trajectory to Orbit

Block V-142 Gyrohorizon

Block V-142 Gyrohorizon

Satellite Deployment System

Satellite Deployment System

The Night-Time Launch of Sputnik-1

The Night-Time Launch of Sputnik-1