|

Even as the Sputnik missions were being built, chief designer Sergei Korolev and academic leader Mstislav Keldysh began planning the missions to send probes to the Moon.

Under the payload code name of "Object-E", probes were designed to impact the Moon and photograph its far side.

The R-7 had been able to launch sizeable payloads into orbit, which requires acceleration to a speed of 7.9 km/sec. However, to reach escape velocity of 11 km/sec, twice the energy per payload mass was needed. To achieve that, the R-7 was augmented by a third stage, and a more accurate guidance and control system was developed. The Three-Stage Luna Rocket

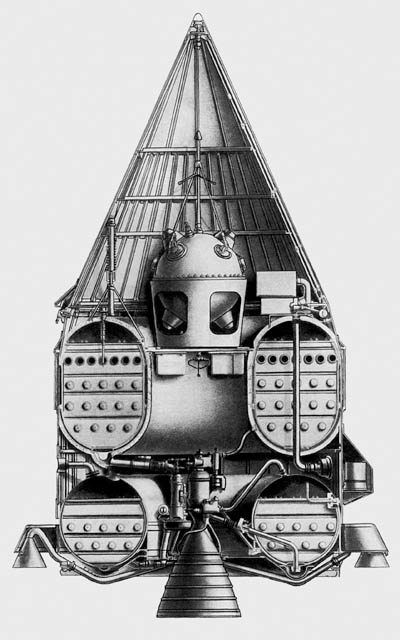

Korolev and his associates began discussing concepts of Lunar missions as early as 1956, but in January of 1958, Mstislav Keldysh sent him a letter outlining specific mission goals, to impact the Moon with a probe and to photograph its far side and transmit the images to Earth by television. The two men convinced the authorities, and a government authorization was issued on March 20. To achieve these goals, the power of the R-7 rocket was augmented by a third stage called Block-E. The resulting rocket was code named 8K72. Because it was designed for deep space, it was referred to publically as a Cosmic Rocket (raketa kosmicheskie). Block-E weighted 1.12 tons and carried 7 tons of kerosene fuel and liquid oxygen in a pair of toroidal tanks. The tanks and engine assembly was also used on the Vostok rocket, to launch heavy manned capsules and surveillance satellites. This new rocket would be able to carry 6 tons into low Earth orbit and 1.5 tons to escape velocity.

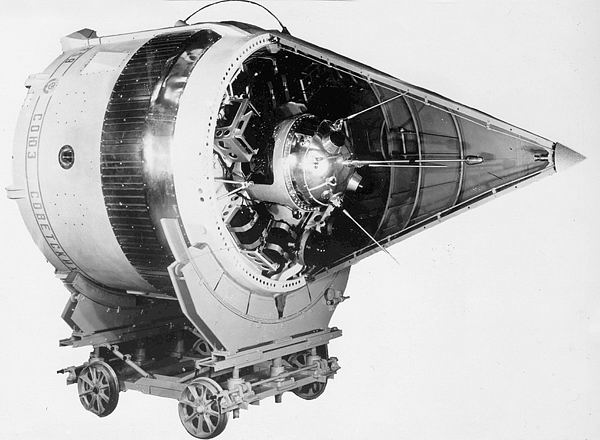

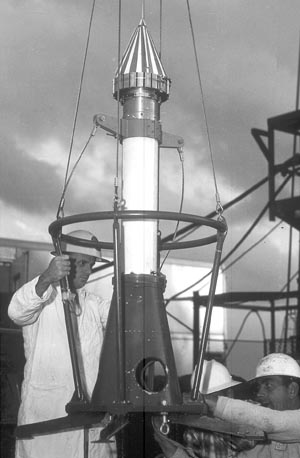

Block-E with Luna-1 Scientific Pod A 5-ton thrust engine, the RD-0105, was derived from the steering engines on the R-7. Although the R-7's main engine was designed by Glushko's firm, Korolev's own people worked with Semyon Kosberg's bureau to augment the R-7 vernier engines with fuel turbopumps and steering jets powered the pump's exhaust. Block-E was developed by Korolev's chief deputy, Vasily Mishin, at the same time as the two-stage R-9 ballistic missile. Both rockets dealt with the problem of how to start a rocket stage in space. In both cases, the upper stage was attached by an open truss, allowing its engine to start while the first stage was still accelerating. Acceleration kept the propellants settled at the bottom of their tanks and prevented bubbles from being sucked into the engine. In addition to the new rocket stage, the retractable scaffold and gantry system at Baikonur had to be lengthened to permit fueling and preparation of the taller rocket. In Siberia, two new telemetry and tracking facilities were constructed at Tartask and Kolpashevo to monitor the flight of the third stage. Tracking and Telemetry Systems

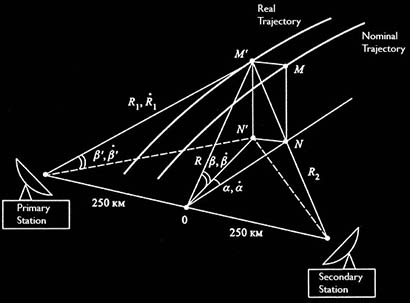

The R-7 ICBM could fly with an autonomous inertial guidance system, but its accuracy was only about 10 km around the target. Using a ground-based radio trilateration and guidance system, accuracy was improved to 2 km. This precision would be vital for the launching of space missions, especially to intercept the Moon. The radio control system operated on 3 cm wavelength and was developed by Yevgeny Boguslavsky, at the design bureau RNII KP. It consisted of a pair of RUP stations (radio control points) situated 250 km on either side of the launch pad in Baikonur. Impulses transmitted by the primary station were returned by an onboard transponder and received by the relay station. Using pulse-return time and doppler shift, this system measured radial distance, lateral devation from the nominal trajectory, and velocity. The lateral deflection of the sustainer stage of the R-7 was controlled with an accuracy of 5 minutes of arc, and the engine cut-offs were timed to give a final velocity accurate to 2 meters per second. When Block-E was engaged, its course was stabilized by onboard gyroscopic sensors. Engine cut-off was either timed by an onboard ΔV sensor (an integrating accelerometer) or by radio control. More accurate Doppler readings of speed could be obtained from a third RUP behind the launch pad in Tashauz, Turkmenistan, but a new system replaced the multi-point radio control system before this was ever really put to use. The Luna rocket was actually based on the new R-7A, a lighter-weight missile with a 12,000 km range. Along with the new rocket came an improve radio guidance system based on a single RUP using interferometry. This was probably used for the Luna missions, which were launched before the R-7A ICBM itself was tested.

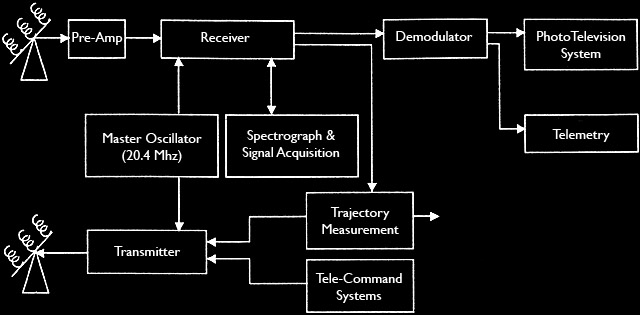

The First Deep Space Communication System For the Lunar missions, a system was needed for tracking the spacecraft position and velocity at great distances. The R-7 tracking and telemetry systems, were only designed to work down range from launch to a distance of where engine cut-off occurred. For the first three Lunar missions, a telemetry system was designed by Evgeny Boguslavsky, the designer of the RTS telemetry system and radio guidance systems used on the R-7. Commands were sent with a 10 kilowatt transmitter on 102 MHz, from a helical antenna array in Simferopol. Telemetry from Block-E and the Luna scientific pod were received in Baikonur, on 183.6 MHz (9/5 times 102) and on shortwave. Luna-3 video was received on 183.6 MHz, using cooled parametric pre-amplifiers and large phased arrays of quadrupoles, mounted on Wurzburg radar turrets. Stations were located on the southern coast of the Crimea and on the Kamchatka peninsula. A large parabolic receiver was under construction in Simferopol, which would eventually replace the Lunar telemetry stations in Baikonur and Crimea. At some point in the Luna program, a pulse system for ranging was replaced by continuous-wave frequency modulation (CWFM). This used a 0.5 second frequency shift of the subcarrior, comparing the outgoing frequency to the returned signal. This used a narrower bandwidth than radio pulses, and so could tune out more background noise and permit greater amplification. The CWFM radio ranging system had an accuracy of 2 km and was called vektor skorosti (vector velocity). It was operated from the station in the Crimea, perhaps using the same antenna later used for Luna-3 video.

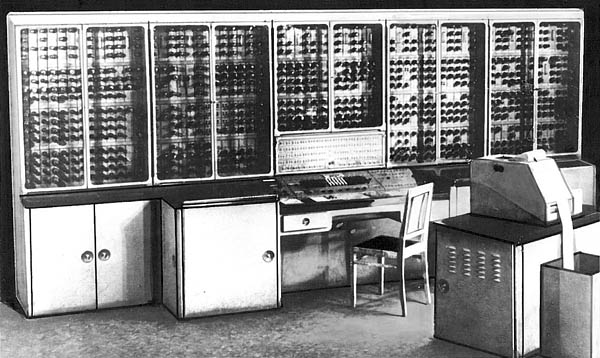

The Ural-1 Computer The first system used by the ballistic control center, for trajectory calculations and analysis, was the Ural-1 computer. This machine contained 800 vacuum tubes, several thousand germanium diodes and a magnetic-drum memory holding 1024 words of data. Real-time flight control of the rocket was most likely performed by another, special purpose, computer. When launched, the R-7 sustainer stage, Block-A, burned for about five minutes. To gain better accuracy of the rocket's velocity, the main engine was cut off early and the final speed was trimmed by burning just the small steering engines. Block-E burned for about seven minutes, and at engine cut-off the stage was about 1500 km above Siberia. From there, it would coast for 34 hours before reaching the Moon. The total payload to escape velocity was about 1.5 tons, which includes the Block-E rocket stage after its fuel was exhausted. The Block-E stages carried a small "scientific pod" that was released after engine shutdown. While we often think of the scientific pod as the spacecraft, both the pod and the rocket stage carried radio and scientific gear and both made the journey to to the Moon.

Rocket telemetry from Block-E was sent with the RTS-8E system on 183.6 MHz. After engine cut-off and deployment of the scientific pod, RTS-8E turned off, and the pod began to send telemetry on the same frequency, using the RTS-12B system. Later, these frequencies were adjusted to be 1.6 MHz different, so both the pod and Block-E could work without interfering. 183.6 MHz telemetry was sent using pulse-time modulation from four short antennas on the top of the pod. They were received at Baikonur on the AFU-U-A-12B antenna system. 120 sensor measurements were repeatedly transmitted at the rate of one per second. As a safety measure, the same telemetry was sent by the Jupter system. After ejection from Block-E, the scientific pods unfurled two steel ribbons to form a V-dipole antenna. These operated on 19.993 MHz (Jupiter-1) or twice that frequency, 39.986 MHz (Jupiter-2, used with Luna-3). Block-E also contained shortwave transmitters operating on various combinations of 19.995, 19.997 and 20.003 MHz on different missions. These signals were sent with pulse-duration modulation, recieved at Baikonur with the AFU-Yu1 directional antenna field. Five rhombic antennas were mounted on wooden poles, aimed to cover a 150° swath of the sky. The 40 MHz Jupiter-2 signal was recieved by a steerable Yagi antenna. Experimental receivers for the Luna telemetry were erected near the Mount Koshka telemetry station, by Vladimir Kotelnikov, Oleg Rzhiga and engineers from the Insitute of Radio Engineering and Electronics. Antennas were dipole and quadrupole Yagi arrays, seen above. The pair of dipole arrays used for 20 MHz was designed to combine the direct signal and the signal reflected off the surface of the water. Systems were tested using the still-active Mayak signal from Sputnik-3.

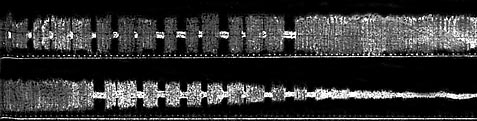

Typical PDM signal (from Luna-2) PDM telemetry consisted of a 7-second syncronization tone, followed by a sequence of 120 values from scientific instruments and spacecraft status. Variation in the signal strength was due to the slow tumbling of the scientific pod. Pioneer/Able Program

At that point in time, Soviet rocket technology was considerably more powerful and accurate. Payload capacity to translunar trajectory of the Luna rocket was more than 100 times that of the Juno II missile used for Pioneer 3 and 4. |

Luna Rocket

Luna Rocket

Block-E

Block-E

Radio Control System for Rocket Launch

Radio Control System for Rocket Launch

RUP Antenna

RUP Antenna

Rzhiga's 20 MHz Antenna

Rzhiga's 20 MHz Antenna

Rzhiga's 40 MHz Antenna

Rzhiga's 40 MHz Antenna

Soviet Lunar Stage, Block-E

Soviet Lunar Stage, Block-E

Pioneer-3 Atop Its Rocket Stage

Pioneer-3 Atop Its Rocket Stage